Previously, we saw a basic machine model in which the program places each object at a different location in memory. We now examine a more structured model, stack-based memory management, that is used by many language implementations.

In most implementations, the data for a function call are collectively stored within an activation record, which contains space for each of the function’s parameters and local variables, temporary objects, the return address, and other items that are needed by the function. In this course, we will generally only consider the parameters and local variables in an activation record, ignoring the other pieces of data there.

In stack-based memory management, activation records are stored in a data structure called a stack. A stack works just like a stack of pancakes: when a new pancake is made, it is placed on top of the stack, and when a pancake is removed from the stack, it is the top pancake that is taken off. Thus, the last pancake to be made is the first to be eaten, resulting in last-in, first-out (LIFO) behavior. Activation records are similarly stored: when an activation record is created, it is placed on top of the stack, and the first activation record to be destroyed is the last one that was created. This gives rise to an equivalent term stack frame for an activation record.

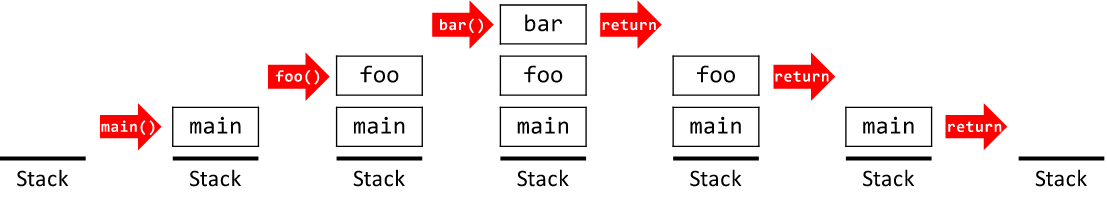

As an example, consider the following program:

void bar() {

}

void foo() {

bar();

}

int main() {

foo();

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)When the program is run, the main() function is called, so an activation record is created and added to the top of the stack. Then main() calls foo(), which places an activation record for foo() on the top of the stack. Then bar() is called, so its activation record is put on the stack. When bar() returns, its activation record is removed from the stack. Then foo() completes, removing its activation record. Finally, the activation record for main() is destroyed when the function returns. The figure below shows the state of the stack after each call and return.

As a more complex example, consider the following program:

int plus_one(int x) {

return x + 1;

}

int plus_two(int x) {

return plus_one(x + 1);

}

int main() {

int result = 0;

result = plus_one(0);

result = plus_two(result);

cout << result; // prints 3

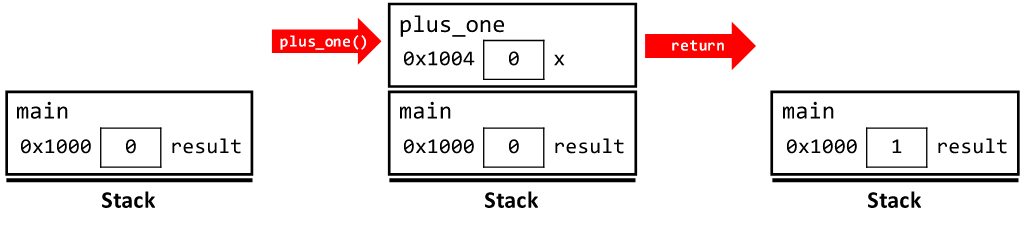

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)At program startup, the main() function is called, creating an activation record that holds the single local variable result. The declaration of result initializes its value to 0, and the program proceeds to call plus_one(0). This creates an activation record for plus_one() that holds the parameter x. The program initializes the value of x to the argument value 0 and runs the body of plus_one(). The body computes the value of x + 1 by obtaining the value of x and adding 1 to it, resulting in a value of 1, which the function then returns. The return value replaces the original call to plus_one(0), and the activation record for plus_one is discarded before main() proceeds. The code then assigns the return value of 1 to result. The Figure below illustrates the activation records up to this point.

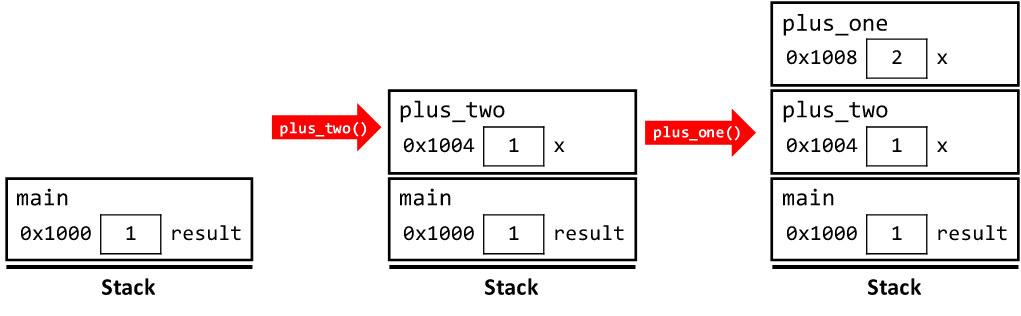

The program then proceeds to call plus_two(result). First, result is evaluated to obtain the value 1. Then an activation record is created for plus_two(), with space for its parameter x. Observe that this activation record is located in memory where the previous activation record for plus_one() was – the latter is no longer in use, so the memory can be reused. After the new activation record is created, the parameter x is initialized with the argument value 1. Then the program runs the body of plus_two().

The body of plus_two() in turn calls plus_one(x + 1). This evaluates x + 1 to obtain the value 2, creates an activation record for plus_one(), initializes the value of x in the new activation record to be 2, and then runs the body of plus_one(). The state of memory at this point is shown in the figure below:

Observe that the new activation record for plus_one() is distinct from the previous one – each invocation of a function gets its own activation record. In addition, there are now two variables x in the program. Within the scope of plus_one(), x refers to the object located in the activation record for plus_one(), and its value is 2. Within plus_two(), x refers to the object in the activation record for plus_two(), and its value is 1.

The invocation of plus_one() computes 3 as its return value, so that value replaces the call to plus_one(), and the activation record for plus_one() is discarded. plus_two() returns that same value 3, so the value 3 replaces the call to plus_two() in main(), and the activation record for plus_two() is discarded. Then main() proceeds to assign the value 3 to result and print it out. Finally, when main() returns, its activation record too is discarded.

Function-Call Process

To summarize, the following steps occur in a function call:

- For pass-by-value parameters, the argument expressions are evaluated to obtain their values. For a pass-by-reference parameter, the corresponding argument expression is evaluated to obtain an object rather than its value. C++ allows references to

constto bind to values (i.e. rvalues in programming-language terms) rather than objects (lvalues). So a reference of typeconst int &can bind to just the value 3, as in

const int &ref = 3;.

The order in which arguments are evaluated is unspecified in C++. - A new and unique activation record is created for the call, with space for the function’s parameters, local variables, and metadata. The activation record is pushed onto the stack.

- The parameters are passed, using the corresponding arguments to initialize the parameters. For a pass-by-value parameter, the corresponding argument value is copied into the parameter. For a pass-by-reference parameter, the parameter is initialized as an alias of the argument object.

- The body of the called function is run. This transfer of control is often called active flow, since the code actively tells the computer which function to run.

- When the called function returns, if the function returns a value, that value replaces the function call in the caller.

- The activation record for the called function is destroyed. In simple cases, implementations will generally just leave in memory what is already there, simply marking the memory as no longer in use.

- Execution proceeds from the point of the function call in the caller. This transfer of control is often called passive flow, since the code does not explicitly tell the computer which function to run.

The following program is an example of pass by reference:

void swap(int &x, int &y) {

int tmp = x;

x = y;

y = tmp;

}

int main() {

int a = 3;

int b = 7;

cout << a << ", " << b << endl; // prints 3, 7

swap(a, b);

cout << a << ", " << b << endl; // prints 7, 3

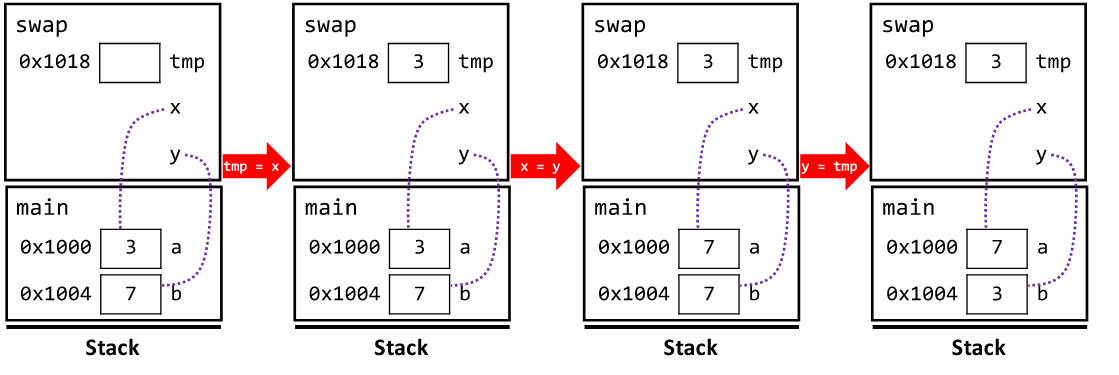

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)The program starts by creating an activation record for main(), with space for the local variables a and b. It initializes a to 3 and b to 7 and then prints out their values. The program then calls swap(a, b), which evaluates the expressions a and b to obtain their objects, creates an activation record for swap(), and initializes the parameters from the argument objects. Since the two parameters are references, the activation record does not contain user-accessible memory for the parameters. (The metadata for the function, however, may include information about the parameters.) The activation record does contain explicit space for the local variable tmp, since it is not a reference. The figure below illustrates the activation record.

Here, the reference parameters are depicted with a dotted line between the names and the objects they reference.

The program proceeds to run the body of swap(). First, tmp is initialized to the value of x – since x refers to the same object as a in main(), the value 3 of that object is copied into the memory for tmp. Then the assignment x = y copies the value 7 from the object associated with y (b in main()) to the object associated with x (a in main()). Finally, the assignment y = tmp copies the value 3 from tmp into the object associated with y (b in main()). When swap() returns, its activation record is destroyed, and execution continues in main(). The latter prints out the new values of 7 and 3 for a and b, respectively.

.